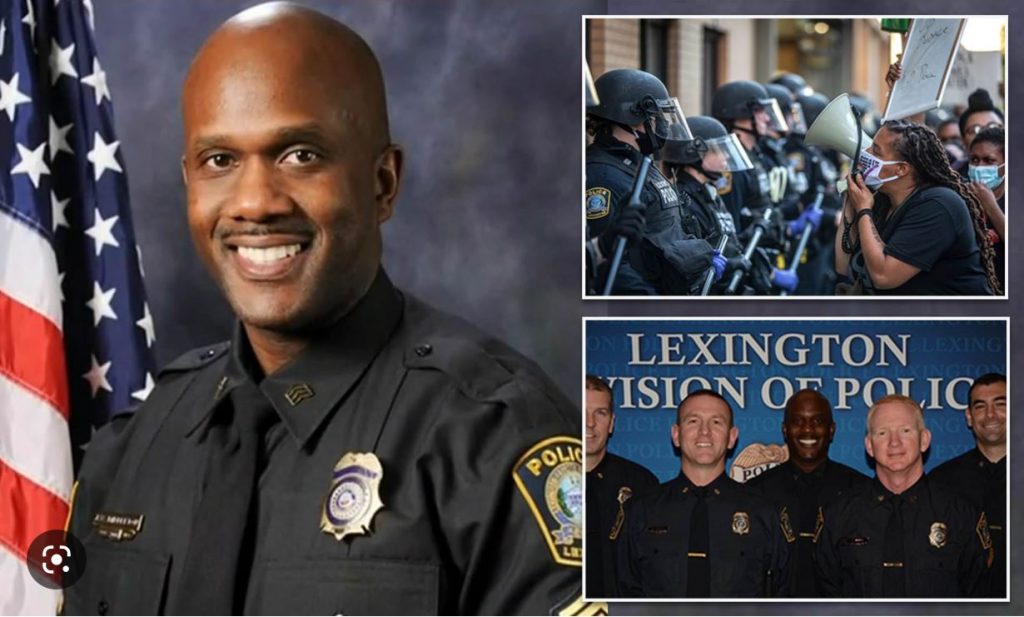

kentucky Cop Jervis Middleton

A Black Cop Sided With Racial Justice Protesters. It Cost Him His Job.

The lonely battle of former Lexington, Kentucky, police officer Jervis Middleton.

On a muggy evening early in the pandemic, Jervis Middleton, an off-duty police officer in Lexington, Kentucky, sat in his cruiser typing determinedly on his phone. The city was tense. One week earlier, a video of white Minneapolis cop Derek Chauvin slowly asphyxiating George Floyd had set off national protests, and Middleton and his fellow officers had been facing crowds of angry demonstrators in the streets for days. The brass had sent out an alert offering overtime to cops willing to work extra shifts.

They are calling some of our folks in, Middleton typed into Facebook Messenger. I gave them a big fat NO again. He added, sloppily, Im about to monitor our radio traffic. He glanced at the message and hit send. He then flipped on his radio and listened for useful intel. He eavesdropped for only a few minutes, according to later testimony from the department’s 911 administrator, but those few minutes would go a long way toward costing him his job.

Police investigators would later conclude that Middleton was conspiring with the enemy, so to speak. At the other end of those messages—obtained from the city through a public records request, along with a trove of documents related to the department’s investigation of Middleton—was his friend Sarah Williams, a local activist. In making the case for Middleton’s firing, the department’s prosecutors would emphasize his radio monitoring and a handful of his messages that they argued included “departmental” or tactical information. Middleton had shared a screenshot, for example, of the internal notice offering overtime to officers. He mentioned at one point that an emergency response unit was rolling out. Another time, he informed Williams he was driving around (off duty) to see if he could spot any plainclothes officers working the crowds—he didn’t.

More broadly, the exchanges, bits of which are redacted, consist of Middleton saying, sometimes literally, “FTP”—fuck the police. The messages channel his sympathy for the protesters and his pent-up rage over racist policing and casual racism within his own department, some of which he claims targeted him directly. He takes issue with the conduct of certain white officers and commanders and feeds Williams embarrassing information about other officers, encouraging her to goad them with it during the protests. I’m not gonna lie…he messaged her at one point. I got emotional when I rode by and watching it through the night! I circled yall while yall were originally in front of the court house… I tried to find out who was [police emoji] in plain clothes but couldn’t see them.. I saw two cocksuckers up by district court, but couldn’t fully make out who they were… I should have went ahead and stood out there… I probably will Sunday.

As a 13-year veteran on a mostly white force, albeit one led by a Black chief, Middleton grappled with dual, and dueling, loyalties. There was the fraternal code, the thin blue line between order and chaos that police profess to protect. But as a Black man, he’d reached a breaking point. The United States is amid “one of the biggest civil rights movements since the ’60s,” he testified at the February 2021 disciplinary hearing that would result in his termination. If “we don’t say something about stuff now, when will we?” The department’s investigators suggested that cops were welcome to their political opinions, but argued that Middleton’s behavior had crossed the line. The city council followed their recommendation and sent him packing.

Black officers in majority white departments “have to do an identity negotiation where you have to decide, are you blue or are you Black? No one else has to do that,” says Tracie Keesee, a co-founder of the Center for Policing Equity who served as a police captain in Denver and later as the NYPD’s deputy commissioner for equity and inclusion. “When you’re with officers of color, you’ll hear them say, ‘I want to be able to make change from the inside.’”

But speaking out, as Middleton knew, risks being sidelined—or retaliated against. (“You got to go along to get along,” he told me.) So when he felt Black and white officers were being treated differently, he didn’t make too big of a stink—officially, anyway. “I’ve seen it a lot, especially now,” Keesee told me. “You report it and nothing happens. There’s an exhaustion. You’re waiting for a new chief, waiting for an administrative change that never comes.”

Lexington, like many American cities, is more racially diverse than its police. Black people make up about 14 percent of the city’s population but only about 9 percent of its sworn officers (50 of 553) as of September. And only 11 Black cops were ranked sergeant or higher.

In the decade prior to Middleton’s firing, citizens made more than 1,000 complaints against Lexington officers. Just 1 in 10 resulted in any formal disciplinary action, and only one cop was fired. (Another officer, who left the department in 2002—and whose supervisor had recommended “strongly” against his reemployment “at any time in the future,” according to a memo obtained by a local paper—was subsequently hired by the Louisville Metro Police Department and participated in the 2020 raid on the home of Breonna Taylor, the Black emergency medical technician whom officers gunned down in her own flat. He was acquitted of reckless endangerment for firing wildly into her neighbors’ apartment, but now faces related federal charges for civil rights offenses.)